Miles Davis Live at the Philharmonic Hall Album Art Gatefold

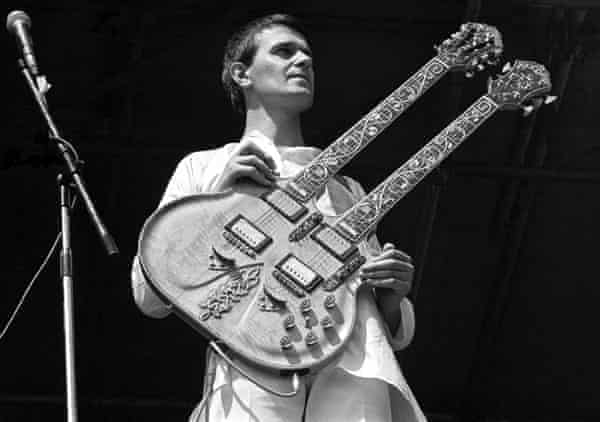

G uitarist John McLaughlin, who helped electrify Miles Davis's music, describes Bitches Brew equally "Picasso in sound". Stanley Nelson, who directed a new documentary on Davis, calls it "an all-out set on", while Davis's official biographer, Quincy Troupe, labels it "a cultural breakthrough: it sounded similar the future".

Fifty years on, it still does. Side by side month will mark the 50th anniversary of Bitches Brew, a pivotal album that altered the trajectory of jazz, messed with the boundaries of funk, and pushed psychedelic rock to new heights of exploration. A double ready released in March 1970, Bitches greatly avant-garde a pattern of progression in Davis's music that snaked back to the showtime of his recording career in the 1950s. The full arc of Davis's sound, and life, forms the basis of Nascency of the Cool, a ii-hour picture created for the PBS series American Masters. (The film, which debuts on 25 February in the United states of america, opens in the Great britain on 13 March and likewise spawned a new soundtrack on Legacy Records.) It covers everything from Davis's ravenous creative development, to his ever-evolving fashion sense, to his complex relationship with women. But a key part of the drama centers on what led up to, and followed, the artistic Vesuvius that was Bitches Brew.

McLaughlin constitute himself a central effigy in that drama immediately later arriving in New York from his abode in Europe at the first of 1969. "I was nervous as anything, with sweat running off me," the guitarist recalled, with a express joy. "I'd simply been in New York for 48 hours and I was with my hero!"

McLaughlin had come to America to join Lifetime, a new band led past Davis's drummer, Tony Williams. But earlier he could offset working with Williams, Davis snagged him, despite the fact that the trumpeter hadn't heard McLaughlin's just-recorded debut solo album, which planted the seeds for what would get the fusion movement. Davis seized on the young McLaughlin purely on the force of Williams having hired him, as well as on his involvement in using an electric guitar on the anthology he was starting to record, In a Silent Way. It was an album that would go nearly as legendary as Bitches. McLaughlin calls the Silent Mode sessions a "baptism by fire".

As shortly as they started recording, Davis gave the young player cryptic instructions, such as "play like you don't know how to play guitar", McLaughlin recalled. "I merely airtight the score and started playing: no rhythm, no harmony, just playing the melody and casting my fate to the air current. He loved it."

Silent Fashion – which also featured fundamental players similar Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul – represented Davis's first all-electric album, following dalliances in that direction the twelvemonth before on the Miles in the Heaven and Filles de Kilimanjaro albums. Though a contemplative and inwards work, Silent Way made a deep impression when it came out in July 1969, encouraging Davis to expand his electrical forays exponentially with Bitches. McLaughlin'due south guitar proved crucial to that expansion. "Miles took me under his wing," the musician said. "I used to become over to his house on West 77th Street and he always wanted me to bring my guitar. I lost count of how many days I spent there, just hanging out. He would striking a couple of chords on the piano and say: 'What do you hear? Practise you hear a riff? A bass line?' In England, I had earned my living playing rhythm and blues, funk and R&B-jazz. So, Miles picked my brain for anything he could chronicle to."

Davis was curious, too, most the new sound of psychedelia. "He was request me about Jimi [Hendrix]," McLaughlin said. "We had played together and I loved Jimi. Miles had never seen him. So, I took him to this art cinema downtown to see the film Monterey Pop where Jimi concluded by squirting lighter fluid on his guitar, setting it on fire. Miles was next to me saying: 'Fuuck!' He was enchanted."

"Miles was being influenced by everything around him," Troupe said. "He was trying to motility his music forrard."

He was motivated, besides, by the changing taste of the public. "1969 was the twelvemonth jazz seemed to be withering on the vine," Davis said in his official biography. "We played to a lot of half empty clubs. That told me something. I started realizing that most rock musicians didn't know anything about music. I figured if they could sell all those records without knowing what they were really doing, I could likewise – just better."

Merely half-dozen months separated the sessions between Silent Way and Bitches. The latter took place over three days in August 1969, ane calendar week after Woodstock. Still, the ii sessions seemed a globe autonomously, given the dense cultural, aesthetic and political changes of the time. "That period was very volatile," McLaughlin said. "The Vietnam war was happening, the whole black-white thing in America … Things were moving very quickly."

When the musicians entered the studio to record Bitches, "it was clear that Miles wasn't sure what he wanted", McLaughlin recalled. "Merely he knew what he didn't want. He didn't desire anything similar what he had washed before. He wanted it more crude and fix. Nosotros didn't really take whatever scores, maybe just some chords he wrote down on a slice of paper from the bag he brought his coffee in. He'd set a tempo and nosotros'd start. Every fourth dimension nosotros hit a groove, a really nice beat, he was happy and then he'd start playing. We just moved from one experiment to the next."

Along the fashion, Davis would throw more inscrutable instructions at the musicians – which again, included Shorter, Zawinul and Corea, forth with the bassist Dave Holland. "'Play the space,' he told me," McLaughlin said, with a laugh. "What does that mean? It was like hearing a koan from a zen master."

But information technology had a positive issue. "It obliged you to remember differently," he said. "You tin can get into musical habits the same way yous get into daily habits. You have to beware of musical indolence. Miles was very much an overseer against musical indolence. He wanted claret and guts and middle all the time."

The subsequent throw-it-at-the-wall arroyo resulted in sections that went nowhere, with parts that had to be thrown out. Consequently, the final album was a collage, assembled from various segments overseen past Davis and producer Teo Macero. "Miles loved Teo," said Troupe. "But, in the end, it was his name that was going to exist on it: he's the creator of this."

The musicians themselves were surprised by some of the final recording. "Sometimes in the studio, you don't see the wood for the trees," McLaughlin said. "But to hear the album, you lot hear information technology all."

And at that place was a lot to hear. Everything almost the music amplified Davis's earlier approach. He featured more musicians that he had ever used before, ofttimes doubling, or tripling, the keyboardists and drummers. "He was opening up from his strict little quartets and quintets," Troupe said. "He had access to a lot of different musicians and he could plug them in someday he wanted to. And they were all young, energetic and different."

The goal, Troupe said, was to create "a maelstrom of music. Everything swirling around him, going in dissimilar directions at in one case. And he was at the centre, directing everything like a mad scientist."

"It was Miles painting with music," McLaughlin said, "and we were all his brushes."

The result gave the music a quality at once unsettling and intriguing. In the long tracks – two of which occupy their own side – the musicians forever seem to exist coalescing around something, moving towards a target without ever quite arriving. It'southward the audio of perpetual discovery, without a terminal destination. "When y'all explore, you don't know what you're going to run into," Troupe said. "It's following your instincts. Music wasn't a final resting place for Miles. It was a fashion frontwards."

At the aforementioned fourth dimension, the music left some of the audition, and sure critics, behind. "At that place's a whole group of people who talk about Kind of Blueish as the be all and end all," Nelson said of that 1959, landmark release. "But Bitches Brew was something new. It appealed to a whole new bunch of fans."

It helped that Clive Davis, the caput of Miles Davis's record company, Columbia, secured gigs for the ring at the Fillmore East. In that location, on bills with the likes of Neil Young and the Steve Miller Band, Davis and his ring wound up out-freaking the hippie freaks. While the trumpeter had taken inspiration from the energy of stone, the way information technology came out of his musicians bore no relation to the genre'southward cliches. "We were looking for new forms of expression," McLaughlin said.

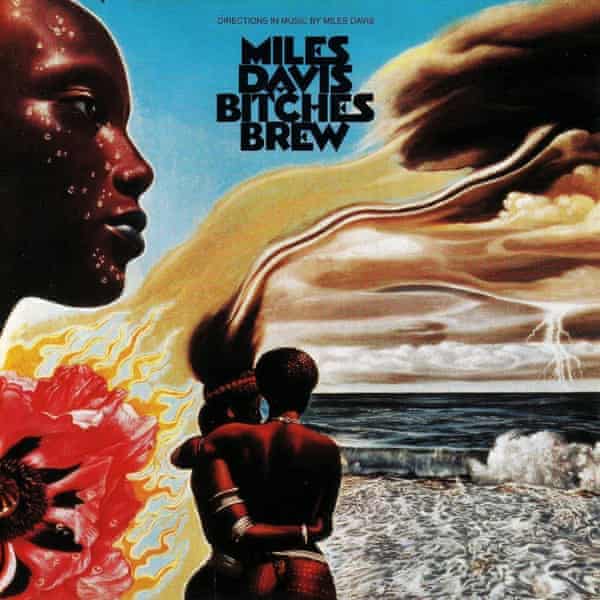

The name given to the issue was fusion, and though some albums that predate Bitches experimented with that approach, Bitches became the movement'south lodestar. The album'southward provocative title and comprehend didn't hurt. The surreal, Afro-futurist paradigm that graced the gatefold cover, created by the German creative person Mati Klarwein, played right into the sensibilities of stoned-out psychedelic stone fans. Inspired by that image, Carlos Santana used a different one by the aforementioned artist for his smash album Abraxis. Santana also began to play music inspired by Bitches, as did acts from the Allman Brothers to Male monarch Crimson to Soft Car. At the same time, the key players from Bitches got such a boost from their contributions to the anthology – which, in McLaughlin's example, included a track named after him – some formed their own bands, including Mahavishnu Orchestra (led by McLaughlin), Return to Forever (with Corea and Bitches drummer Lenny White) and Weather Report (featuring Shorter and Zawinul). Bitches became Davis's fastest-selling album, moving 500,000 copies in its kickoff year, and more than 1m units since. It likewise pointed the way to even harder music by the star, like Music from Jack Johnson, whose sonic violence presaged punk-jazz, and On the Corner, which went deeper into funk and also brought in Indian influences.

All of that experimentation was brewed on Bitches. "Ultimately, the anthology tin can exist looked at in several ways," said Nelson. "Information technology launched a whole new way of thinking almost jazz, and information technology was very influential with stone musicians. At the same time, information technology can exist taken simply for the swell sounds it contains."

-

Birth of the Cool will show in the United states of america on PBS on 25 February and volition be released in the United kingdom on 12 March

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/feb/24/miles-davis-bitches-brew-50th-anniversary-film